A new study finds that food allergies are most common among communities of color and people at lower socioeconomic levels.

Food allergies are very common. As of 2021, about 20 million people in the United States had food allergies, reports the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America.

The new research polled, via online and telephone surveys, 51,819 U.S. households—or 78, 851 individuals—from October 2015 through September 2016 with a view to determining how the burden of food allergies in the nation might split along demographic lines.

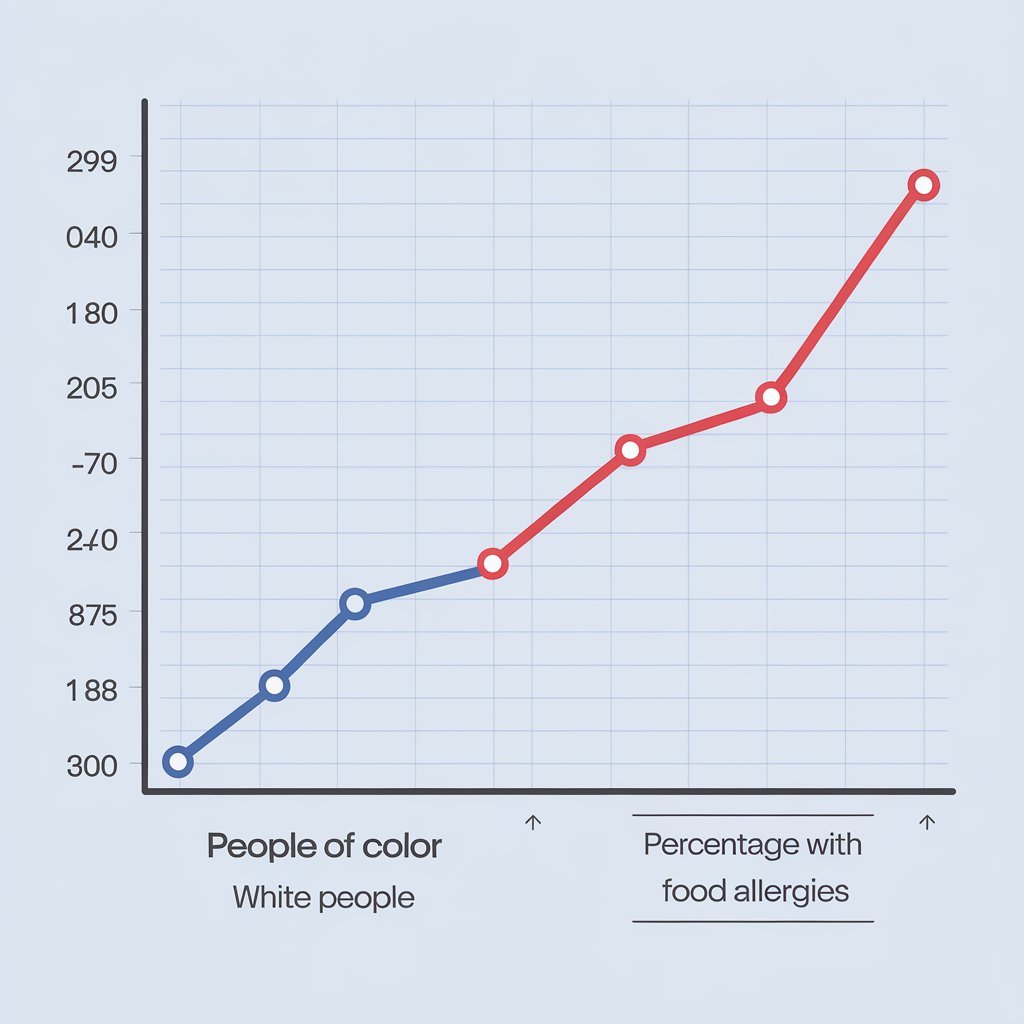

The team found that Asian, Black, and Hispanic people were most likely to report having food allergies compared with their White peers, while food allergies were evidenced less in households at the highest income brackets.

When looking at the data, Jialing Jiang, a lead study author who is a research project manager in the Center for Food Allergy & Asthma Research (CFAAR) at Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine said that the group suspected that a few racial and ethnic groups might experience more food allergy burden, something that complemented other research across the U.S., United Kingdom, and Australia.

With this said, the latest research gave a fuller picture.

“Past studies didn’t allow generalization due to a lack of a representative sample size, study design, and comparison of groups,” Jian explained. “We certainly didn’t think White people would have the lowest prevalence of food allergy among the other races and ethnicities since food allergy has been widely researched among the white population.

The Role Race and Ethnicity Play in Food Allergies

As presented in a summary of some of the results, the lowest percentage of self or parent-reported food allergies was for non-Hispanic White across all ages, which was 9.5% compared with Asian participants, Hispanic participants, and non-Hispanic Black participants at 10.5%, 10.6%, and also at 10.6% respectively.

The study also indicated that non-Hispanic Black respondents were the most likely to report allergies to multiple kinds of foods, amounting to 50.6% of the respondents. Asian and non-Hispanic White people showed the lowest rates of severe food allergy reactions compared to other groups, at 46.9% and 47.8%, respectively.

When asked what might account for these ethnic and racial demographic differences, Jiang said it is currently “unclear” why Asian, Black, and Hispanic people seem to experience more food allergies than their White peers.

Possible hypotheses include diet, cultural practices and norms, environmental factors, and genetics.

Ruchi Gupta, MD, MPH, also a co-author and the Mary Ann & J Milburn Smith Senior Scientist in Child Health Research and Director of CFAAR, professor of pediatrics and medicine at Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine, as well as clinical attending physician at the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago agrees with those suggestions adding that food one is always having as being a core element of their diet, the period when specific food was introduced in their diet and the environment itself are some possibilities.

According to Ahila Subramanian, MD MPH FAAAAI FACAAI of Food Allergy Center of Excellence Cleveland Clinic “The exact cause of food allergy is still unknown, but it has been indicated that there are various factors contributing to the emergence of a food allergy.

She explained race and socioeconomic status, having another allergic disease, infant feeding practices, delaying solid food in diet, and less exposure to microbes—such as in urban vs. farm dwellings—to all potentially impact a person’s susceptibility to food allergies.

Subramanian, unaffiliated with this research, said the underlying potential for allergies to be tied to genetics and epigenetics is a possibility as well.

There’s a big question mark over why one person might develop food allergies compared to another,” said Julie Wang, MD, pediatric allergist-immunologist, professor of pediatrics at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and a clinician and clinical researcher at the Jaffe Food Allergy Institute. “More research needs to be done to understand how sociocultural and economic factors impact food allergy prevalence, management, and outcomes.

It’s important we get a better understanding of this to outline clear strategies for addressing entrenched disparities,” Wang told Health.

Socioeconomic factors at play.

When it came to socioeconomic status, the study showed that, among households that had a yearly income of above $150,000, there were the lowest levels of prevalence of self or parent-reported food allergies: 8.3%.

According to Subramanian, when considering this, it is necessary to know that actually, socioeconomic status and race “are closely linked.”

“Having financial access to afford a regular supply of ‘safe’ foods is crucial for the successful management of food allergy and reducing the incidence of food allergy reactions,” Subramanian said.

Jiang said financial resources can have a wide-ranging domino effect on how people can manage their allergies. For instance, having a current epinephrine auto-injector (EAI) prescription was more common among people with higher household incomes and the use of EAIs was higher in those with higher household incomes.

“Emergency department visits for food allergy reactions in the last year and in a lifetime were highest for those in the lowest household income bracket, possibly due to barriers in food allergy management,” she said. “While it is not in the scope of our study, previous studies have suggested that financial access to more resources allows better access to allergen-free foods to manage food allergy.

Analyzing Allergy Prevalence by Demographic

Jiang said some of the more common food allergies among the different groups surveyed are peanuts, shellfish, milk, and tree nuts-all the same types of allergens that commonly cause reactions among the U.S. population in general.

On the other hand, data suggested that racial and ethnic groups suffer from certain types of allergies more than others do.

For example, peanut allergy is higher in Asians. The least common was shellfish, which is allergic to the white population.

Subramanian explained that this survey goes along with other research out there that shows a “slightly higher prevalence of certain food allergies by race.

This fact is important: “these findings have not been consistent across studies,” she noted.

Subramanian added cultural dietary norms appear to play an important role as well.

“For instance, allergy to finned fish is seen more often in countries with higher consumption of fish like Australia, Spain, and Portugal compared to the United States,” she said.

Another example can be seen in Greece where the incidence of peanut allergy is very low compared to the overall global incidence of peanut allergy. Interestingly peanut is not a common ingredient in Greek cuisine.

Improving Food Allergy Treatment

Subramanian says that once a food allergy is diagnosed for a patient, the treatment plan is “avoiding the culprit allergen and preparing the patient” in case they react.

Understanding the socioeconomic background of an individual is important to give an effective treatment plan for managing the allergy.

“Financial means impact the ability to treat a food allergy reaction via access to medications such as the epinephrine autoinjector, as well the ability to provide a nutritionally balanced diet to the patient via alternative foods, without the culprit food, that is often more expensive,” Subramanian said.

She says this study is the first to bring to light the health disparity in food allergy outcomes by race and socioeconomic background. And now with this open door to understanding, more needs to be done with such research.

Looking back on the new study, Jiang said it was limited in that they were unable to analyze “subpopulations” and categorized some groups into one category for the purposes of analysis. Future research “should consider the further cultural differences and diversity within racial and ethnic groups experiencing food allergies and explore their unique food allergy burden.”

“It would be great to follow families over time from the actual initial diagnosis and better understand environmental factors, family history, genetics, microbiome, etc.,” she said. “We need a better full picture.